Priest-Pioneer: The Heritage American Archetype

Forging a Nation, Facing Its Fall: Our Heritage at Stake

Introduction

Heritage Americans are not only a unique ethnicity, but also an archetype, what I call the “Priest-Pioneer.”

Priest-Pioneers instinctively carry out divine order (Priest) and explore new physical and philosophical frontiers (Pioneer) to build earthly civilizations that seek to approach heavenly ones.

This Friday on the Fourth of July let’s not ask WHAT made America great, but rather WHO made America great. The answer is Heritage Americans, because they were Priest-Pioneers.

Providence has guided the Northwestern European, (primarily British Isles) settlement of North America. Over centuries, our ancestors built a new, better world with the United States of America, (and to a smaller extent, Canada). Today we make America great again by awakening our inherent Priest-Pioneer spirit. To that end I will share anecdotes from my ancestors who demonstrated the Priest-Pioneer archetype across the discovery, settlement, and frontier expansion epochs of the United States.

Settlement of the Colonies: Building the Priest-Pioneer Society (1600–1770s)

A Brutal Beginning

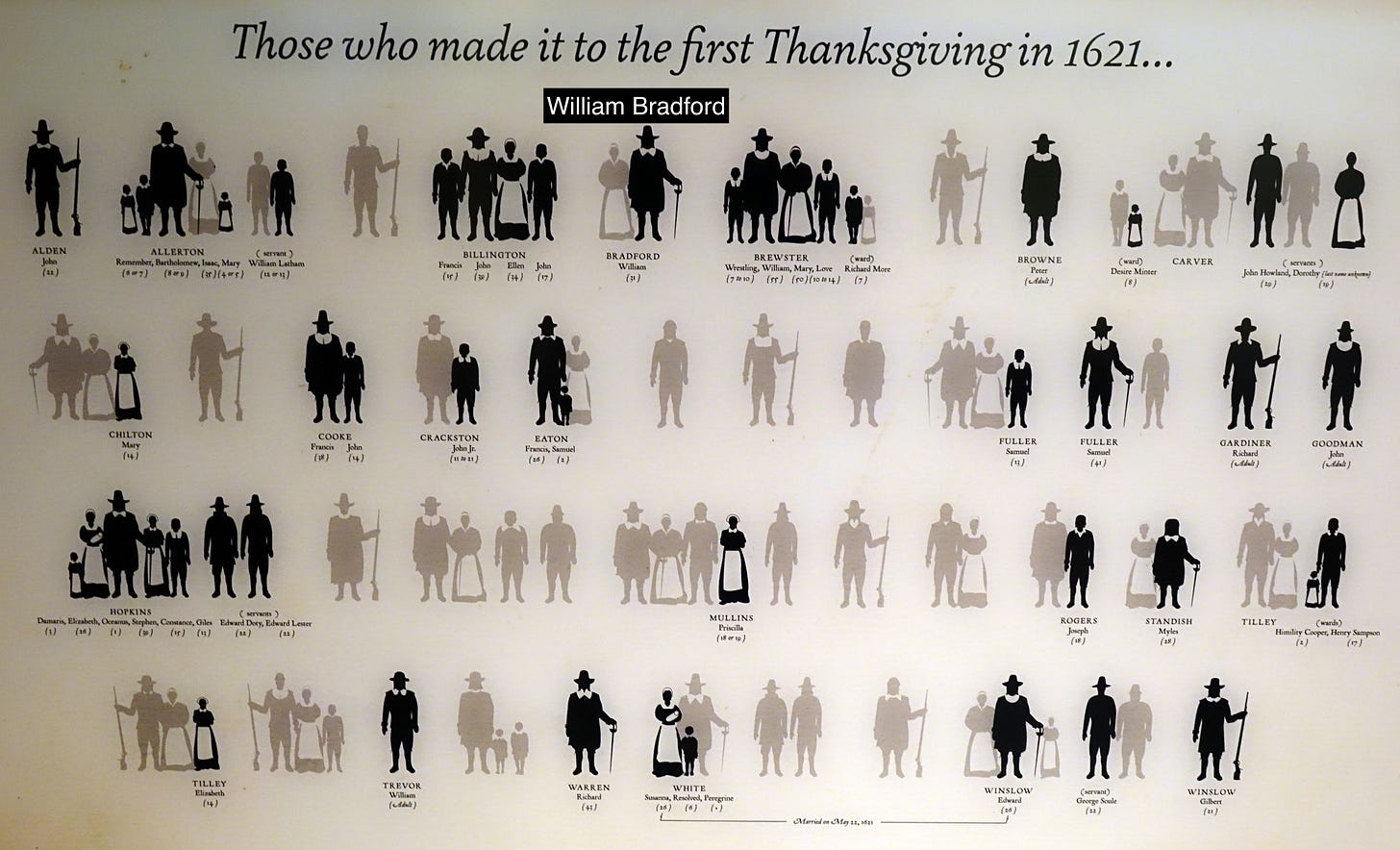

Plymouth's first winter tested the resolve of my 11th great-grandfather, Governor William Bradford.

Born in 1590 in Austerfield, Yorkshire, to a farming family, he was orphaned by 12. Drawn to the Separatist movement, which rejected the Church of England's corruption, he fled to Leiden, Holland, in 1608 at age 18 to escape King James I's persecution. There, Separatists faced poverty and feared losing their English roots. By 1620, seeking a new home, Bradford joined 101 passengers on the Mayflower for a 66-day voyage.

During the voyage storms battered the ship. Scurvy spread. They landed at Cape Cod on November 9, far north of their Virginia grant, settling Plymouth by December 21, 1620.

"Being thus arrived in a good harbor... they fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean."

—William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation, Book I, Chapter X

On November 11, 1620, he co-authored the Mayflower Compact, the first governing document of Plymouth Colony. The Mayflower lay at anchor in Provincetown Harbor, positioned within the hook at Cape Cod's northern tip, when 41 of its 101 passengers signed the Mayflower Compact on November 21 [O.S. November 11], 1620.

That first winter was merciless. Cold, disease, and malnutrition killed 45 of 102 settlers by spring. Bradford, sick but enduring, rallied survivors, distributing scant rations and overseeing crude shelters built in frozen soil.

Elected governor in 1621 after John Carver's death, Bradford served until 1657. In March, with Squanto's aid, he forged a treaty with Wampanoag leader Massasoit, securing peace. That fall, a three-day harvest feast with the Wampanoag—later called the First Thanksgiving—marked survival. Bradford's Of Plimoth Plantation chronicled these trials.

Why It Matters

William Bradford embodies the pioneer-priest archetype.

His flight to Holland and treacherous Mayflower crossing show pioneer daring—embracing uncharted lands despite storms and disease. Leading through a deadly winter, he organized shelter-building and food distribution, displaying frontier resilience. The Mayflower Compact was a pioneer act of innovation, creating order in wilderness. His priest qualities—faith in divine providence—drove the Compact's covenant, rooting governance in moral ideals.

The Wampanoag treaty, guided by his belief in God's will, ensured survival, blending spiritual purpose with pragmatic leadership. Bradford's dual role as explorer and moral anchor laid America's foundation, a testament to the pioneer-priest spirit that shaped a nation.

Founding of the Nation: Codifying the Priest-Pioneer Vision (1770s–1820s)

Defiance at Bunker Hill

My 7th great-grandfather John Graham defied tyranny at the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Born around 1730 in Londonderry, New Hampshire, to Scots-Irish immigrants from Ulster, he was raised Presbyterian, steeped in ideals of liberty. In 1764, he settled Hancock, clearing dense forest for a farm with his wife and children.

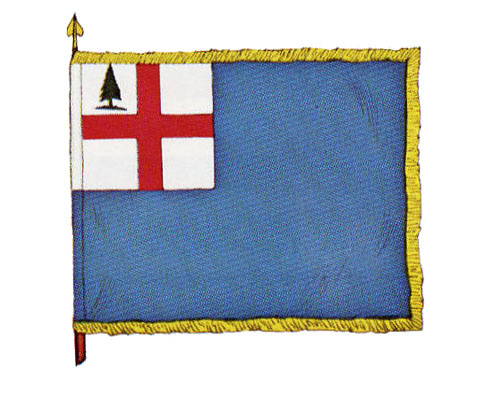

By 1775, British taxes like the 1765 Stamp Act fueled colonial unrest. Graham joined Captain William Scott's Minute Men in Peterborough, trained to mobilize instantly. On June 16, 1775, word came of British troops advancing toward Boston. Graham's unit marched 20 miles overnight, reaching Breed's Hill by dawn. Under Colonel William Prescott, they dug trenches and piled logs for a redoubt, finishing as British ships opened fire from Boston Harbor.

At 3 p.m., 2,200 redcoats charged. Graham fired his musket from the redoubt, smoke burning his eyes. The colonials repelled two assaults, killing or wounding over 1,000 British soldiers. By the third wave, ammunition was gone. Graham hurled stones as redcoats scaled the defenses.

"[He] seized stones, and began hurling them at the enemy, and not without effect."

—History of Peterborough, p. 29

A musket ball grazed his leg, drawing blood, but he fought until Prescott ordered retreat. The battle cost 140 colonial lives and wounded 271, yet it rallied the cause. Graham returned to Hancock, farming until his death around 1790.

Why It Matters

Graham's stand captures the pioneer-priest archetype.

His grueling march and trench-digging under fire reflect pioneer grit—risking life for a new nation. Throwing stones when ammunition ran out shows frontier ingenuity, a refusal to surrender. His Scots-Irish roots fueled a pioneer ethos of independence, driving him to defend his community. His priest nature—rooted in Presbyterian beliefs—cast liberty as a divine right, a sacred cause worth bloodshed. This conviction helped forge a nation grounded in justice and self-governance.

Graham's sacrifice links the pioneer's boldness with the priest's duty, shaping America's founding principles.

Westward Expansion and Manifest Destiny: Extending the Priest-Pioneer Frontier (1830s–1870s)

Faith Under Fire

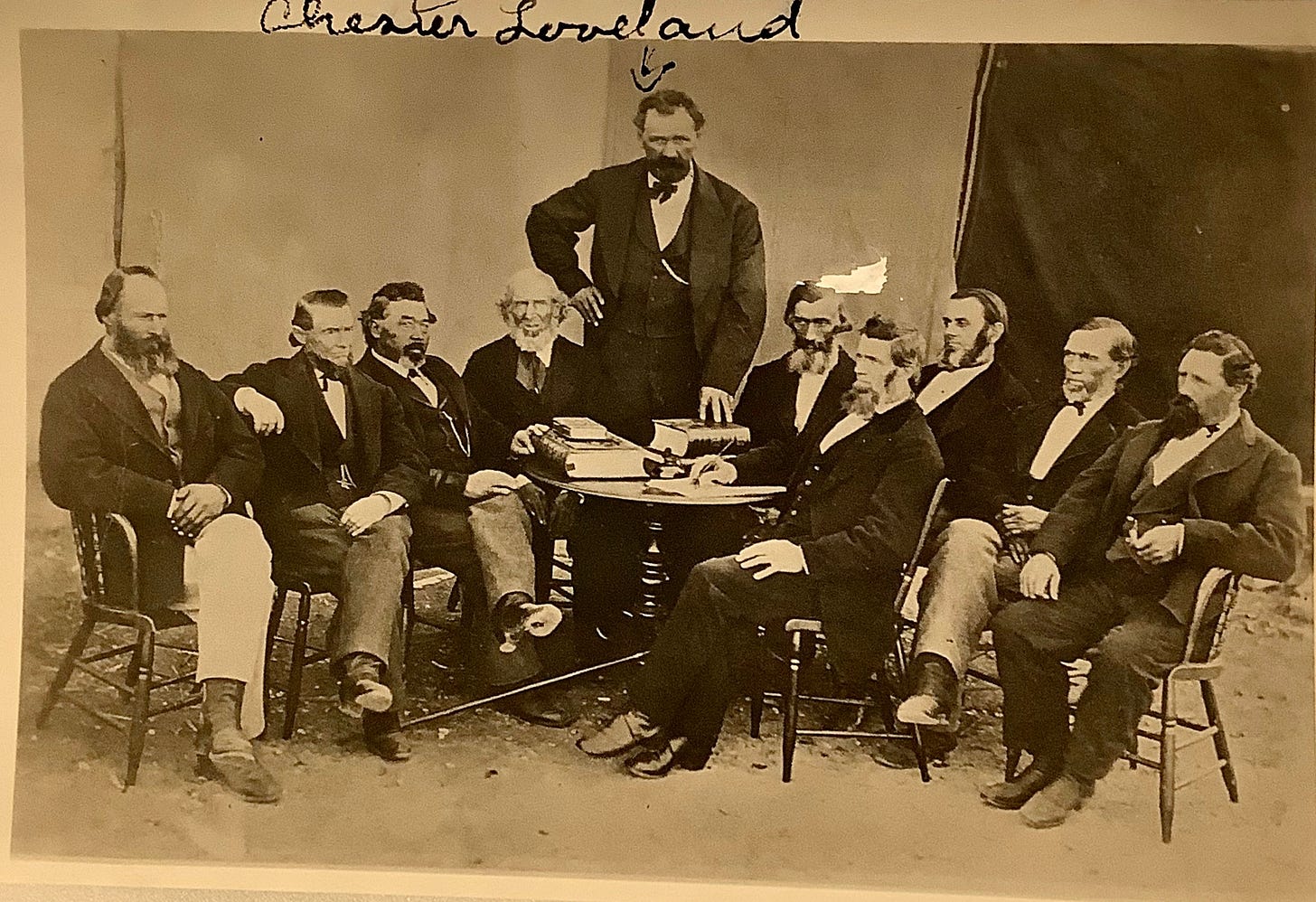

My 4th great-grandfather Chester Loveland faced persecution for his faith.

Born in 1817 in Madison, Ohio, traced his lineage to William Hills, who immigrated from Essex, England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1632 aboard the ship William and Francis.

The average height of white American males around Chester’s time was approximately 5 feet 7 inches (174 cm), relatively tall by global standards of the time. An unnamed descendant described Chester Loveland:

He was six feet two inches high, weighed 240 pounds, had blue eyes, a high forehead, and brown curly hair. When in his military suit and mounted on his high horse, he was the admiration of all. He was a stranger to fear, and he never shunned positions of danger when duty called to rescue either friend or foe. He acquired considerable wealth during his life.

In 1837, he joined the LDS Church in Kirtland, Ohio, and moved to Warsaw, Illinois, near Nauvoo, by 1840. In June 1844, after Joseph Smith's arrest, anti-Mormon locals demanded Loveland help seize him. He refused. On June 24, a mob tied a rope around his neck, dragging him toward a tree; a neighbor's quick action freed him.

As a Nauvoo Legion captain, he led 50 men on nightly patrols. In late 1844, during a skirmish by the Mississippi River, a vigilante's bullet grazed his arm, leaving a scar.

"One bullet grazed Chester's left arm, tearing his sleeve and leaving a visible burn mark from the friction and heat."

—William Loveland, family account, 1920

In 1850, Loveland joined the Warren Foote Company's 103-wagon trek from Kanesville, Iowa. The 1,000-mile journey was brutal. On August 15, his son George, 8, died of cholera and was buried near Ash Hollow, Nebraska. Arriving in Salt Lake City on September 17, he settled in Bountiful, producing charcoal from Wasatch timber. By 1859, he moved to Brigham City, served as its first mayor from 1866 to 1870, and managed a 160-acre farm at Call's Fort, growing wheat and barley, while serving as a church high councilor.

Why It Matters

Loveland's trials embody the pioneer-priest archetype.

His 1,000-mile trek, enduring cholera and burying his son, mirrors the pioneer's grueling frontier quests. Surviving mob violence and a skirmish shows tenacity, like a frontiersman facing mortal threats. Building farms in Bountiful and Brigham City reflects pioneer ingenuity—transforming deserts into communities. His priest faith—refusing to betray Smith, serving as a councilor—reflects moral steadfastness. As mayor, he built a religious haven in Brigham City, embodying the priest's call to lead with virtue. Loveland's blend of endurance and spiritual duty extended the pioneer-priest archetype across the American West, forging a legacy of faith and resilience.

80 Years of Domestication

By the late 19th century, westward expansion ended, and with it, the frontier opportunities and great struggles that had long shaped Heritage Americans' sense of purpose faded. Over the next 80 years, industrialization and urbanization dominated, narrowing the scope for exploration and heroic endeavor. Life stabilized, but the pioneer-priest archetype—marked by bold discovery and moral vision—lost its outlet. Then, in the 1960s, the space age began. Neil Armstrong's 1969 moon landing offered Heritage Americans a new arena to channel that dormant spirit, reviving the drive to explore and the call to a broader human mission.

Modern Echoes of the Priest-Pioneer: The Space Age (1960s)

Per Aspera Ad Astra

Neil Armstrong reached the heavens. I wish I could call him my ancestor.

Born in 1930 in Wapakoneta, Ohio, to Scots-Irish descendants from 1700s Pennsylvania, he was captivated by flight, earning his pilot's license at 16. He flew 78 combat missions as a naval aviator in the Korean War, honing skills that led him to NASA in 1962.

On July 16, 1969, he launched aboard Apollo 11 with Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins. On July 20, Armstrong piloted the Eagle lunar module to the moon's surface, navigating treacherous terrain, and announced, "The Eagle has landed." Stepping onto the lunar soil, he spoke his iconic words.

"That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

—Neil Armstrong, July 20, 1969

He and Aldrin planted a plaque: "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon, July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind." They returned safely on July 24.

Why It Matters

Armstrong's lunar landing captures the pioneer-priest archetype.

Navigating the Eagle through space's void mirrors the pioneer's daring, akin to settlers crossing oceans. His precision under life-or-death risks reflects frontier resilience, honed by years as a test pilot. The plaque's inscription—"We came in peace for all mankind"—and his iconic words cast the mission as a priest-like act, uniting humanity in a moral vision beyond national triumph. Rooted in Scots-Irish heritage, Armstrong extended the pioneer-priest legacy into space, blending bold exploration with a higher purpose that echoes America's founding spirit.

Conclusion

The pioneer-priest archetype defines ethnic American exceptionalism.

Heritage Americans carry the pioneer-priest spirit of our forebears, who tamed frontiers and built a nation. But we do not face open plains or lunar seas—only ethnic replacement and national destruction through unchecked immigration by those who scorn our ethnic heritage. The pioneer-priest archetype demands bold defiance, yet we falter. Will we channel Bradford’s resolve and Armstrong’s daring to halt this tide? Or will cowardice doom our people to fade from the earth?

Providence has been the silent architect animating our nation. But our enemies have us outnumbered and outgunned. We all feel it. It’s overwhelming. To be blunt, we can’t succeed without help from higher powers. Like our Revolutionary War ancestors who faced overwhelming odds, we must make an appeal to heaven.

Despite all of our deep flaws and disastrous mistakes, America is still the best hope for mankind. That is why, for centuries, the entire world has sought to live here. If ethnic Americans fail our nation, where will the world turn to for freedom and prosperity? Who else but Heritage Americans have the founding blood and spirit and help from the other side of the veil sufficient to triumph over the greatest existential threat we’ve ever faced?

As conditions in the USA worsen, foreign aliens and non-ethnic Americans can just go back to their home countries.

But America is our homeland, we have nowhere else to go.

Rise, Heritage Americans—save our nation or lose it forever.