Who Are Heritage Americans?

The Founding Ethnicity That Built America: From Jamestown to the End of the Frontier Era

In an era of mass immigration and demographic transformation, understanding who Heritage Americans are has never been more urgent. These descendants of the Founding Americans—Protestant, English-speaking, Northwestern Europeans who built the nation from Jamestown through the 1870s—represent more than ancestry. They embody a distinct American ethnicity forged through centuries of frontier experience, constitutional development, and cultural synthesis. As America grapples with questions of identity and belonging, recognizing Heritage Americans as the foundational stock provides essential context for the future of our nation.

OVERVIEW

Heritage Americans are the descendants of the Founding Americans— Protestant, English-speaking, Northwestern Europeans, primarily English, who birthed the American nation, starting from Jamestown in 1607 to approximately the 1870s. This nearly three century period includes the discovery, settlement, and frontier expansion epochs of the United States.

The Founding American era wound down by the 1870s for two reasons. First, America transitioned from a frontier, developing nation into a fully modern, industrializing one, with mature, metropolitan areas and infrastructure from coast to coast.

The second reason is demographics; significant waves of immigrants who were not Protestant, English speaking, from northwestern Europe, and who did not assimilate with the Founding, ethnic Americans. As I will discuss later, they were and are “Hyphenated Americans” with dual foreign ethnic and religious loyalties.

Heritage Americans are Ethnic Americans.

THE AMERICAN ETHNICITY

The Founding Americans gave birth to a new nation, but also a new ethnicity— the American ethnicity. Genetic descendants of the Founding Americans are Ethnic Americans:

Protestant

English speaking

Northwestern European ancestry

So, Heritage Americans are the TRUE Native Americans. The American ethnicity developed over three centuries and formative eras of the nation:

Colonial

Forging of the Nation

Western Frontier

Colonial Period

The American ethnogenesis began in the Jamestown Colony and is rooted in Anglo-Saxon heritage, evolving into Anglo-American culture in the New World. English companies and royal charter holders established all early colonial settlements (even New Amsterdam, founded by the Dutch in Manhattan, came under English control by 1664). Most colonists were of English origin, and their descendants formed the majority of the early American population. While other ethnic groups were present in colonial America—with Germans representing a significant minority—their increased presence largely resulted from immigration waves during the 1700s.

By 1790, the white American ethnic composition across all states was as follows:

British Isles, 86%

60% English

4% Welsh

22% consisting of: Scottish (5%), Irish (6%), or Scotch-Irish (11%)

German: 9% (notably in Pennsylvania)

Dutch: 3% (notably in New York and New Jersey)

French Huguenots: 2% (notably in South Carolina and New York)

Swedish, less than 1% (notably in Delaware and New Jersey)

Thus, 95% of all white Americans in 1790 were descendants of the peoples of the British Isles and Germany.

The distribution of these groups varied by region:

New England Colonies (Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut): Heavily English, with smaller numbers of Scots-Irish and other groups.

Middle Colonies (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware): More ethnically diverse, with large English, German, Dutch, Scots-Irish, and Swedish populations.

Southern Colonies (Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia): Predominantly English, with Scots-Irish and smaller numbers of French Huguenots and Germans.

The American ethnos developed into two varieties across the thirteen founding colonies; northern and southern, (but with some blending in the Middle Colonies).

Northern Colonists (WASPs): Primarily English, Scottish, and Dutch settlers in New England (e.g., Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay). Defined by Puritanism or Anglicanism, English language, and northwestern European ancestry. Emphasized communalism, education, and a "covenant" theology.

Southern Colonists: Predominantly English and Scottish settlers in colonies like Virginia, Carolinas, and Georgia. Also Protestant (mostly Anglican, some Presbyterian), but shaped by a plantation-based, hierarchical society reliant on slavery. Cultural traits included English language, aristocratic traditions, and a strong sense of regional honor.

Northern WASP and Southern White ethnicities both emerged from Protestant, northwestern European roots but diverged due to geography, economy, and social structure. Northerners emphasized community and moral purpose, while Southerners embraced hierarchy and honor. Their shared race and contributions to American nationality linked them, but ethnic differences—Puritan vs. plantation culture—highlighted distinct identities within the early U.S. Cultural traits included English language, aristocratic traditions, and a strong sense of regional honor.

Forging of the Nation

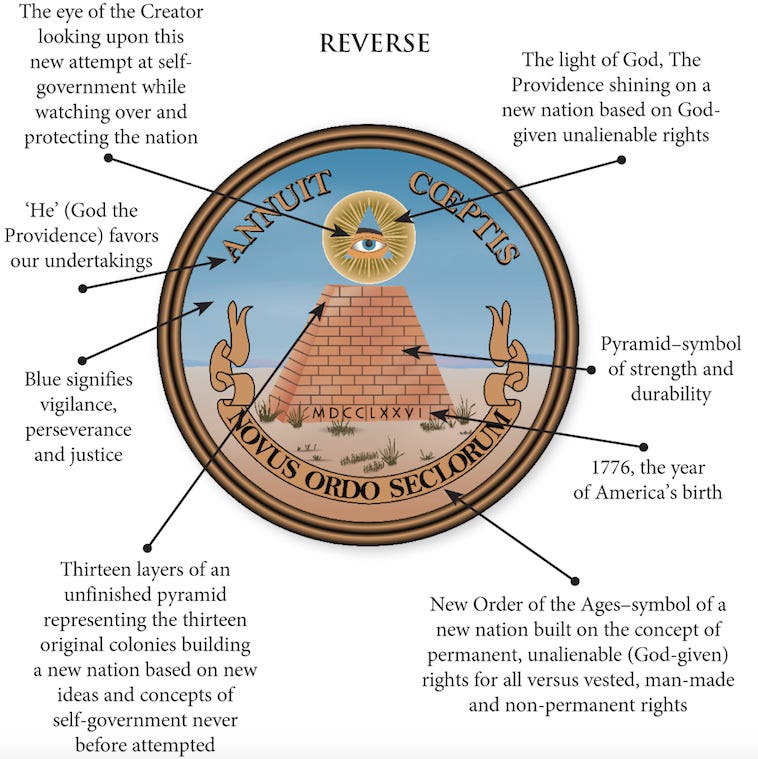

The Revolutionary War and subsequent founding of the United States quickened the American Colonial ethnicity into a new independent and autonomous, American nation ethnicity. On July 4th, 1776 the Continental Congress announced the Declaration of Independence. During the session, members of the Congress determined the new nation needed a formal seal to affix on official documents. The Great Seal of the United States, “…reflects the beliefs and values that the Founding Fathers attached to the new nation and wished to pass on to their descendants.”

The seal illustrates the foundations of the American Nation Ethnicity:

Ethnicity, and to a lesser extent religion, were so important to the the definition of an American, that the Naturalization Act of 1790 was ratified before the Bill of the Rights (in 1791). The Naturalization Act provided that any “free White person” who resided “within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States” for at least two years could be granted citizenship if he or she “showed good character” and swore allegiance to the Constitution.

When interpreting the Naturalization Act, courts linked “Whiteness” with Christianity, effectively barring Muslim immigrants from citizenship until the 1944 Ex Parte Mohriez case granted citizenship to a Saudi Muslim man.

Western Frontier

In the first half of the 19th century, as the United States expanded west beyond the thirteen colonies, the American ethnicity continued to be Protestant, English-speaking, and of Northwestern European descent. British ancestry, continued to dominate, but new regional sub-ethnicities formed, such as Germans settling the Ohio River Valley, Scandinavians the upper Midwest, and Mormons pioneering the Intermountain West. Irish concentrated in urban centers like New York and Boston.

The settling of the western frontier came in a spirit of Manifest Destiny.

In the 1850s, The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855, and colloquially the Know Nothings, rose targeting Catholic immigrants, especially Irish, fearing their loyalty to the Pope. The party sought to curb immigration, restrict foreign voting rights, and marginalize Catholic influence in politics.

HYPHENATED AMERICANS

1880 is a reasonable point to mark the the end of Founding Americans and the start of the modern, industrialized nation and the arrival of a wave of foreigners who became known as the “New Immigrants” who, as citizens, became “Hyphenated Americans.”

Earlier immigrants (pre-1860, often called “Old Immigrants”) were mostly from Northern and Western Europe, predominantly Protestant, English-speaking, and more likely to have skilled jobs and some wealth. They assimilated more easily and often arrived as families.

The “New Immigrants” (post~1880) from Southern and Eastern Europe, including Italians, Poles, Hungarians, Russians, Greeks, and Jews, were more likely to be Catholic, Orthodox, or Jewish, spoke little or no English, and often came from rural, less industrialized backgrounds. They tended to be poorer, less literate, and more likely to arrive alone as young adults seeking work.

Many “New Immigrants” settled in rapidly growing cities in the Northeast and Midwest, such as New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, often forming distinct ethnic neighborhoods.

These immigrants and their descendants are not Heritage Americans, not Native, Ethnic Americans, but Hyphenated Americans. These are immigrants with dual loyalties and identities, such as Italian-Americans, Greek-Americans, Polish-Americans, Jewish-Americans, etc. Few Hyphen Americans assimilate.

Here are notable quotes from U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt about "hyphenated Americans" primarily from his 1915 speech to the Knights of Columbus in New York City:

- The one absolutely certain way of bringing this nation to ruin, of preventing all possibility of its continuing to be a nation at all, would be to permit it to become a tangle of squabbling nationalities, an intricate knot of German-Americans, Irish-Americans, English-Americans, French-Americans, Scandinavian-Americans or Italian-Americans, each preserving its separate nationality, each at heart feeling more sympathy with Europeans of that nationality than with the other citizens of the American Republic.

- The men who do not become Americans and nothing else are hyphenated Americans; and there ought to be no room for them in this country.

- The man who calls himself an American citizen and who yet shows by his actions that he is primarily the citizen of a foreign land, plays a thoroughly mischievous part in the life of our body politic. He has no place here; and the sooner he returns to the land to which he feels his real heart-allegiance, the better it will be for every good American.

- There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American. The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.

The shift to Hyphenated Americans led to increased nativist sentiment and the growth of anti-immigrant movements, as established Americans worried about the newcomers’ ability to assimilate and their impact on American society.

The Immigration Act of 1882 established the first federal immigration oversight, imposing a head tax on each immigrant and excluding “undesirables” such as convicts, lunatics, and those likely to become public charges. It laid the groundwork for further federal immigration control

The US immigration acts of the 1920s, notably the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924 (Johnson-Reed Act), aimed to drastically curb immigration from non-Western European countries. Immigration from Asia was completely banned, and immigrants from the Western Hemisphere were exempt from quotas. European immigration fell from 4.5 million (1910–1914) to under 800,000 (1925–1929).

These acts were explicitly designed to preserve the existing ethnic makeup of the US by drastically limiting arrivals from Southern, Eastern Europe, and Asia, while maintaining higher quotas for Northern and Western Europeans.

IDENTITY AS AN INHERITANCE

In "Wise Men Have Left Us an Inheritance," Ben R. Crenshaw defines "heritage America" through seven foundational inheritances that collectively form American identity.

Crenshaw identifies the English language as the first inheritance, arguing it provided a unified means of communication essential for American civilization. He warns of its decline through increased bilingualism and advocates making English the official language.

Christianity constitutes the second inheritance, with Crenshaw challenging claims of colonial religious decline by citing evidence that 56-80% of founding-era Americans were "churched," with 98.1% of congregations being Protestant. He argues America is "normatively Christian" at its core.

The third and fourth inheritances—self-government and Christian government—reflect America's tradition of local political autonomy informed by explicit Christian principles. Crenshaw contends that colonial and founding documents demonstrate intentional Christian governance.

Liberty, the fifth inheritance, is defined not merely as freedom from constraints but as "spiritual freedom" to choose moral good within community contexts. Crenshaw rejects modern individualism as false freedom.

The sixth inheritance, equality under law, derives from America's Christian-English legal tradition, establishing principles like presumption of innocence and trial by jury.

Finally, Americans' relationship with the physical land shaped their character through necessity of community survival, widespread property ownership, and frontier influence.

Throughout, Crenshaw maintains that rejecting these inheritances means repudiating authentic American identity. He argues that heritage Americans must embrace these foundational elements that make America unique.

I disagree with Crenshaw’s view that non-Whites can be Heritage Americans; but they can be patriotic and exceptional Americans nonetheless.

Ally Americans

Before I close, I want to mention a third category of Americans—those who are not Heritage Americans but who unequivocally support Heritage America and who do not hold dual ethnic or religious loyalties. I call these citizens, “Ally Americans”. They can be of any ethnicity or faith or immigration vintage. But they advocate for America remaining a predominantly White, Christian nation governed by the spirit and letter of America’s founding documents.

An imperfect example of an Ally-American is Stephen Miller, Trump’s White House deputy chief of staff for policy and the 12th United States homeland security advisor. Mr. Miller was born in California into a Jewish family. His maternal ancestors emigrated from modern day Belarus to the United States around 1903–1906.

Elon Musk would be an Ally American if he didn’t so passionately advocate for legal immigration and siding with Indians while mocking Heritage Americans and committing deboosting and censorship tactics against opposition. Tragic.

CONCLUSION

Defining Heritage Americans provides more than historical clarity—it offers a framework for understanding American identity moving forward. These descendants of the Protestant, English-speaking, Northwestern European Founding stock represent the continuing thread of the original American ethnicity. They are joined by Ally Americans who, regardless of their own heritage, champion the foundational principles and demographic stability that created American exceptionalism. This isn't about excluding others from citizenship or patriotism, but about recognizing the specific inheritance that made America possible. As the nation faces unprecedented demographic change, acknowledging Heritage Americans and their role in preserving foundational culture becomes not just historically accurate, but practically essential for maintaining the civilization our ancestors built.

I would agree with virtually all of this. I would just slightly disagree with your treatment of the Irish. The Americans of Irish descent in 1790 who made up 6% of the population are markedly different from those Irishmen who arrived post-1840. Of those of Irish descent in 1790, the vast majority were Protestant and most were of Anglo-Irish or non-Irish Gaelic descent. They assimilated very well into Anglo-American culture as they were almost indistinguishable from English and other Protestant British descended Americans. However, the Irish who arrived en masse, post-1840 were predominantly of Gaelic descent and were Catholic. Most settled in urban centers such as New York, Boston, and Chicago. They formed ethnic enclaves and did not assimilate. They continued to identify as "Irish-American" and even openly resented and hated the native Old Stock Americans. They created many of the corrupt Democrat political machines such as Tammany Hall. Some even wanted to create almost exclusively Irish cities, such as in Boston in the late 19th century. In Boston's case, they wanted a "Dublin on the coast of North America;" they wanted a city with very few WASPs. I would argue that this group has not fully assimilated to this day. It is not that they could not, but simply that they haven't. They continue to identify as "Irish-Americans" and hate WASPs.

1870? What?

No. The founding fathers were very clear in the preamble to the Constitution: "Ourselves and our Posterity."

That's it. You don't get to put words into their mouths or make things up. Heritage Americans are those who are descended from the people who fought in the American Revolution *and that is it.*

Nobody who came here afterward, nobody who was a loyalist.